- Home

- Elizabeth Little

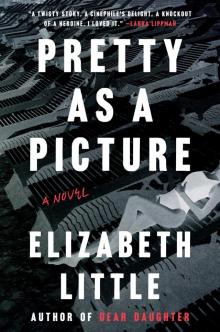

Pretty as a Picture Page 8

Pretty as a Picture Read online

Page 8

For the past fifteen minutes, Anjali has been guiding me through the seemingly identical carpeted hallways that crisscross the hotel’s lower level. I have long since lost my bearings, not to mention my breath. I’m also not sure if she’s just fucking with me.

I knew I was in trouble the moment we stepped out of the elevator and were confronted with a sign detailing the litany of amenities to be found on the lower level: salon, spa, pool, squash courts, yoga studio, gallery, theater, wine cellar, cigar lounge, and others I forgot immediately. The list put me in mind of an apology that goes on too long, the kind that gets you into more trouble than you were ever in to begin with.

The deeper we descend into the hotel, the more completely I’m convinced that I am never going to find my way out—which is a problem. Because there’s a non-zero chance I’ll be fired as soon as Tony sees my face, and if that happens, I’ll want to know the quickest way out of this place. If I’m going to be humiliated, I’m going to do it as God intended: alone, sitting in my shower. I do not want to spend the rest of my life in a broom closet or a laundry room or a service elevator, and, yes, I’m catastrophizing, I know—I know. But panic isn’t Rumpelstiltskin. Simply naming it doesn’t make it go away.

I make a fist and dig it hard into my hip.

We take a right, a left, another right and come, at long last, to a door. It’s glass, diamond-paned, opaque, with big bronze handles shaped like crescent moons. Anjali hefts it open.

On the other side is a vast room, longer than it is wide, with a two-story ceiling tiled in lapis and burnished gold. Centered on the far wall, flanked by crimson curtains, is a small concession stand.

I rub my eyes with the heels of my hands and wait for my vision to clear.

Yes, Virginia, it really is a movie theater.

“Told you,” Anjali says, smugly.

Unlike the lobby, it isn’t in mint condition. The lingering scent of cheap chocolate and butter-flavored topping isn’t enough to mask the faint, wet-sock smell of developing mold. The crimson and gold scallop-patterned carpet is so threadbare I can feel the subfloor through the soles of my shoes. Part of me wants nothing more than to take a bottle of Windex and some newspaper to the mirrors that line the wall.

Even so, I would’ve killed to work in a place like this. Of all the old movie theaters in my hometown, only two are still operating, and one of those didn’t reopen until it was time for me to leave for college. So when I set out to get a job as an assistant projectionist, I didn’t get to work at the Orpheum or the Lyric or the Rialto. I had to settle for the Carmike Beverly 18.

“It’s beautiful,” I say.

Anjali looks up and around, blinking a little, as if she’s still surprised to find herself there. “Yeah,” she says, “it doesn’t suck. I guess the original owner of the hotel married an actress back in the day. He built this so she could screen her movies.”

“Would I have heard of her?”

“Doubt it. She had a bit part in Rebecca, but that’s about it.” She points to a black-and-white headshot hanging above the nacho cheese warmer. “That’s her. Violet fake-French-name-I-can-never-remember. She’s ninety-seven and still kicking—maybe you’ll get to meet her. Here we are. Keep it down, okay? They’re rolling.”

“Wait—what?”

She opens the door to the auditorium and pushes me through.

I lurch forward, grabbing the back of a chair to keep from falling over. As soon as my legs remember how to move, I dart to the side and flatten myself against the wall, unable to keep a curse from hissing out between my teeth.

Some editors insist on isolating themselves from the vagaries of daily production. I’m not one of them. I don’t have a problem seeing actors out of character or knowing a particular shot was a pain in the ass. I’m not precious. Still, I try to avoid physically being on set. Like I said, sometimes I mix up movies and memory—but it can go in the other direction, too. I’ll see something in real life and then, later, in the editing room, I’ll think I’m remembering coverage and will dig around in my files for the footage only to realize it’s not there. It’s inefficient, and it makes me feel silly. I don’t like it.

Also, if people know I’m on set, they might try to give me notes.

But I can’t do anything about it now, so I grab a seat, house left, as far from the crowd at Video Village as I can get.

In an art form dependent on the smooth coordination of a thousand different moving parts, the mosh-pit chaos of Video Village—which in this case consists of three monitors bungee-tied to a hotel room service cart—really stands out. There are a dozen people there even now, jockeying for position, pushing up against one another for a better view of the screens even though, really, the only people who need to see real-time footage are the director and the DP. Not the PAs. Not the grips. Certainly not the man in crisp jeans and pristine sneakers that everyone seems to be ignoring—the executive who interviewed me, I realize.

Amy always says that one of the hardest parts of her job is finding a way to focus on the footage when she’s at Video Village, surrounded by gawkers angling for a better look. I heard once that Oliver Stone cloaks his monitor in Duvetyn, that he disappears beneath it like an old-time photographer ducking under a heavy black focusing cloth. So when the camera’s rolling, no one’s watching the feed, no one’s watching him. It’s just him and the rectangle.

Amy insists she’d never be able to get away with something like that. Because that is the actual hardest part of her job, she says: having to appear to be endlessly accommodating without actually accommodating anyone at all.

I crane my neck forward, trying to see through the scrum. Where’s Tony?

“Liza, focus.”

I whip around and there he is, down in front, stepping back from behind the camera, an ARRI Alexa on a carbon-fiber tripod. The sight sends a shiver through me. Of course he’s operating the camera himself. Why would he relinquish control of anything to anyone? He’s going to fight me over every single cut—assuming I make it that far.

He hops up on the small stage, joining Liza and another actress I don’t immediately recognize. Liza’s wearing jean shorts over the orange swimsuit from the beach scene, along with black, T-strap character heels, a style I haven’t seen since I spot-opped my tenth-grade production of Anything Goes.

The other actress, an older white woman, is dressed in a bobbed platinum wig and a beaded silver dress. She’s probably pushing seventy, but she has the calves of a twenty-year-old dancer. Eileen Fox, that’s her name. She’s a stage actress—she won the Tony last year for Mother Courage. Or maybe I mean Hedda Gabler?

A Broadway import’s a mixed blessing. She’ll hit her marks perfectly but forget which line she sipped her drink on. Hopefully Tony doesn’t give her too many close-ups. Too often stage actors new to film overdo it on camera and end up looking less like real faces than state-fair gourds that eerily resemble faces.

I realize then that they’re projecting a movie onto the screen behind Liza and Eileen.

Judith Anderson, Joan Fontaine.

Rebecca.

I reevaluate the tableau in front of me, slotting in the new variables and recomputing. Eileen must be playing Violet, the actress-wife of the hotel magnate. And I guess in this scene they’re rehearsing?—but for what?

Something dreadful occurs to me then, and I come up on my feet, scanning the room for any elaborate sound equipment. But I don’t see any floor mics. No one’s setting up playback.

I put my hand to my heart. I think I’m safe.

If this had turned out to be a musical, I really think I would have had to fire Nell.

On stage, Tony shoos away the makeup artist who’s trying to blot Liza’s nose and stares down at his lead actress.

“I’d love to know what you think you’re doing.”

Liza smooths her hair behind her ear. “I’m doing what you told me

.”

He leans in, but his words carry all the way back to the cheap seats.

“And here I thought I told you to act.”

Tony steps away, and the makeup artist hurries back in, fussing with Liza’s lip color and murmuring words of encouragement until Liza’s shoulders detach themselves from her ears. By the time the hairstylist joins them, Liza looks almost confident.

Eileen has retreated stage left, where she’s leaning against the proscenium, arms crossed, head tilted back, one elegant ankle crossed over the other. The makeup artist makes a half-hearted move to touch up her foundation, too, but Eileen waves her off.

Tony ducks back behind the camera, and a hush falls over the room.

“Places,” he says.

A flurry of movement: Eileen and Liza get into position, finding their light, tipping their chins and twisting their hips, hitting their angles. The sound guy presses one hand against his headphones; his other hand hovers over his mixing board. A man with long black hair and an intense expression—he must be the DP—makes a complicated series of hand gestures. A moment later, an electrician adjusts a bounce card. The DP shakes his head and motions to them to lower it back down. At Video Village, the executive low-key hip-checks a PA.

And—again—we wait.

The silence lasts no more than thirty seconds, but the suspense is unbearable.

“Liza,” Tony says then, and I’m amazed she doesn’t start at the sound. “Your left foot needs to come an inch stage left.”

Liza slides her foot to the side.

“An inch, not a centimeter.”

She moves it a bit more.

“Acceptable. Eileen, you’re perfect, as always. Roll sound.”

The sound guy nods. “Sound speed.”

Tony settles in behind the camera. “Petra, mark it.”

An assistant camerawoman slides into frame with a timecode slate. She calls out the shot number and the take—39, yikes—and claps the slate. Then, a collective indrawn breath.

I find myself leaning forward.

“Action.”

When I’m reviewing footage, working on an early cut, I hear these words a thousand times a day—more, maybe. Action, cut, action, cut, action, cut, action, cut. These aren’t commands, not for me. They’re more like everyday punctuation. A capital letter. A period. An indication that I should pay attention to what’s going on in the middle. Actors and on-set crew, though, they have a more visceral, Pavlovian response. I’m pretty sure if you went to any coffee shop in Santa Monica and shouted “Places!” half the customers would freeze.

I’d really forgotten how different it is to be here in person.

Action.

Breathe in.

Cut.

Breathe out.

It’s almost biological.

Maybe I’m too used to thinking of myself as the one who brings a movie to life. Too in love with the idea that, until it gets to me, a scene’s just a play that someone happened to record. Maybe I’ve forgotten what an audacious act of creation this is—how exhilarating it can be to share this moment with a group of my peers, fellow film lovers all, each of us so passionate about our craft and our art and our—

The boom mic wobbles as the operator tries to hide a yawn with his elbow.

Three rows ahead of me, the makeup artist is texting on her phone. Two women from the art department sit slumped against a wall, whispering to each other behind their hands. I think one of the sound guys is literally asleep.

Well—it was a nice moment for a second there.

The image behind Liza and Eileen starts to flicker, then goes dark. Half the room turns to look at the projection booth; the other half turns to look at Tony.

“Exactly how often is this going to keep happening?” he asks.

“I’m doing the best I can!” the projectionist shouts down. “This thing has a mind of its own!”

“I’m delighted to hear that one of you does.”

After a moment, the projector whirs back to life with a metallic screech that I feel in the back of my teeth. Tony circles a finger in the air. Everyone resets.

I tug at my earlobe. My ear’s itching.

“Action.”

Finally, Liza and Eileen get to run their scene. It’s a cute shot: the two of them, dwarfed and doubled by the images of Joan Fontaine and Judith Anderson. A little on the nose, maybe, but I’m willing to give Tony the benefit of the doubt. The lighting helps. The tungsten bulbs the DP’s using are slightly out of fashion, but the quality of the light sure is something. This guy has chops.

Not that he’ll ever hear that from me.

Liza misses another cue. I don’t catch what Tony says to her this time, but we all hear what she snaps in response.

“Well, maybe if I could get a decent night’s sleep, I’d be able to remember my blocking.”

Tony tilts his head to the side, considering. “Eileen seems to be doing just fine.”

Eileen nods sagely. “Earplugs and Ativan.”

Tony presses his eye to the viewfinder and lifts his hand.

I tug on my ear again.

“And act—”

“Wait.”

The voice comes from the rear of the theater. It’s a white woman, about fifty years old, tall and solid and strong. She reminds me powerfully of my mother. I wonder if her forearms, too, are lean and freckled from a lifetime of being the first one to roll up her sleeves and get things done. She’s standing just inside the door, lips pinched into oblivion.

Tony steps out from behind the camera, and I shrink back, sure he’s going to unload on this nice normal woman.

“Francie,” he says, warmly. “What did we get wrong?”

She nods in Eileen’s direction. “Her makeup,” she says. “My grandmother has worn bright red lipstick every day of her life since she was thirteen. She says no one should have to face the world without it—she even wears it in bed. She taught herself to sleep on her back so it wouldn’t smudge during the night.”

I catch myself reaching for my ear for the third time.

Tony turns, clears his throat. “Carmen? This is your area of expertise, I think.”

The makeup artist drags her eyes up from her phone. She looks at Tony, then turns to Francie. “You know what brand she used?”

“Elizabeth Arden. Victory Red.”

“Do you have that in your kit?” Tony asks.

Carmen props her chin on the heel of her hand. “I don’t carry vintage stuff. You know who did, though? Penelope.” She takes a beat. “Too bad you fired her.”

Any good humor in Tony’s expression vanishes in an instant. His lips shape a smile that’s the stuff of nightmares. “Now there’s an interesting idea.”

Carmen sighs, stands up. “Yeah, fine, I can replicate it. Give me ten.”

There it is again. That itch in my ear—except it’s not an itch. It’s a high-pitched whine. Faint, but definitely there. I glance over at the sound guy. He’s clutching his headphones and frowning. I wave at him, trying to get his attention, but he’s too focused to see me.

I think it’s getting louder.

I pull myself to my feet. “Tony?”

Tony turns, blinks. “Who’s this?”

The whine is definitely higher now. Like it’s about to—

I swallow. “I think there might be something wrong with the genny.”

His eyebrow lifts. “I wasn’t aware we’d hired a new electrician—”

Pop.

I glance up; Tony does the same. We just lost a light.

Out of the corner of my eye, I see the DP take a tentative step forward.

Pop.

Two lights now. A small band of crew members rush the stage, but they’re not quick enough, because—

Pop pop pop pop pop.

&nbs

p; A series of small explosions, one after the other, like a strip of cheap firecrackers.

We lose all the lights.

And then, the projector goes out.

Darkness.

—followed by the clatter of forty-odd phones switching on, bathing the room in a pale glow.

“Everyone okay?” someone asks.

“I don’t know,” Eileen says. She’s drawing on her stage voice now, and its round, rolling tones fill the room. “Does ‘covered in fucking glass’ count as ‘okay’?”

A few seconds later someone finds a light switch, and then we’re blinking into the amber murk thrown off by the theater’s ancient house lights.

We all readjust—

And the room explodes into motion. Most of the crew members hustle over to the stage, where Liza and Eileen are still crouched down, their hands protecting their faces.

Anjali bursts through the door, shouting something into her phone and motioning urgently to a nearby PA. She stalks over to the DP, who immediately puts his hands up in a defensive gesture.

“Don’t look at me like that,” he says. “I triple-checked the setup—personally. It was perfect.”

“Perfect,” she says, shaking her head in disbelief.

A burst of static behind me; I glance back over my shoulder. A broad-chested man in khaki pants and a sports coat is standing just inside the lobby door, speaking into a radio, his hand shielding his lips from view. Next to him is Isaiah. He’s sliding his gun back into its holster.

He catches me watching him. He has the grace to look a little sheepish.

“Tony!”

Onstage, Liza has pulled herself to her feet; two crew members are trying to help Eileen up, their hands cupped beneath her elbows, but they’re thwarted by the slim cut of her dress. There’s simply no way to lift her without risking indecent exposure.

Eileen swats their hands away and tugs her skirt higher on her hips, exposing the tops of her stockings. “For God’s sake, I’m not precious. I did a twelve-week run of The Graduate.”

Three members of the hair department race in. They comb their fingers carefully through the women’s hair, picking out shards of glass.

Pretty as a Picture

Pretty as a Picture