- Home

- Elizabeth Little

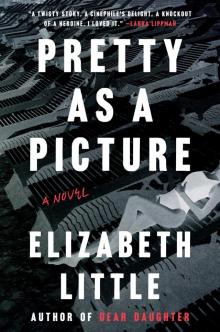

Pretty as a Picture Page 6

Pretty as a Picture Read online

Page 6

“No idea.”

I smile. This one’s my favorite.

“You can get a drink out of a coconut.”

I steal a look at his lips, and my fingers go still. He’s smiling, too—and here’s a rare sensation, a current that zips along the top of my cheekbones, right where Amy tells me I’m supposed to put highlighter. An image of Humphrey Bogart and Claude Rains shimmers behind my eyes.

I reach up and rub the feeling away.

“And what about editors?” Isaiah asks. “What do people say about them?”

I glance at him, startled. “Honestly? Not much.”

“There must be something.”

“Most of the jokes about editors come from other editors, which means they don’t meet what I’m given to understand is the technical definition of a joke.” I pause. “In that they’re not actually funny.”

“Oh, come on. Try me.”

“Fine. But don’t say I didn’t warn you.” I rearrange myself in my chair, tucking my legs up under me. “How many editors does it take to change a lightbulb?”

“How many?” Isaiah asks.

“None, it’s fine like that! Move on!”

I can tell right away: It doesn’t land. Isaiah’s still smiling with his mouth, but his eyes have uncrinkled at the corners. As usual, I should have quit while I was ahead.

Except then he surprises me.

“I know we only just met,” he says. “But that doesn’t sound like you at all.”

I draw my ponytail back over my shoulder and wrap it around my palm.

“No,” I say. “I guess it doesn’t.”

SUZY KOH: Okay, so, Isaiah, the 64,000-dollar question: Why didn’t you tell Marissa that she might be in danger?

ISAIAH GREENING: As long as she was with me, she wasn’t.

GRACE PORTILLO: But don’t you think she had a right to know what she was getting herself into?

ISAIAH GREENING: You have to understand, my job is to manage fear. And that requires as much psychological finesse as operational expertise. Making sure that a client is safe and that a client feels safe are often two very different things. For most of my clients, particularly a certain kind of businessman, that means bells and whistles. The best tech, the biggest guys—over-the-top black-ops bullshit, you know? Even if I’m just escorting them to a forty-grand-a-plate charity function in the Hamptons. [pause] Marissa, though—she’s not like my regular clients.

SUZY KOH: Well, yeah. For one thing, she didn’t even know she was a client.

ISAIAH GREENING: But I would’ve lost my job if I’d told her. And I knew I was absolutely the best person for that job. I really didn’t have a choice.

SUZY KOH: Are you trying to argue that you were doing her a favor by keeping her in the dark?

ISAIAH GREENING: If I’d told her the truth, she never would’ve gotten on that boat. And then where would we be?

SEVEN

The island sneaks up on me.

Bet you didn’t know an island could do that. But this one does, and not just because I’ve been doing my best not to look at the water.

It sits just barely above sea level, broad and flat, skimming across the water like an oil slick, the two-story buildings along the shoreline concealing the bulk of the island from view. There’s not much else to look at: A modest lighthouse sits atop a crumble of rock just south of the docks; to the north, a roller coaster and Ferris wheel peek out from behind a cluster of trees. In the distance, on the far eastern end of the island, is a rambling, hulking structure—a hotel, if I’m lucky. A hospital, if I’m not. It’s too dark to trace the specifics of its outline, but I’d guess every light in the place is turned on: I count forty-seven visible windows in three higgledy-piggledy clusters. This has to be our destination.

Only a film crew would waste that much electricity.

“What’s this place called again?” I ask Isaiah.

“Kickout Island.”

I eye the building in the distance. “It’s not a penal colony, is it?”

“It was kijkuit, originally. From the Dutch.” The captain’s standing at the top of the ladder. His gaze lands briefly on me before skittering away. “It means ‘look out.’ You might want to find something to hold on to, we’ll be docking shortly.”

“Look out?” I say. “What for?”

But the captain doesn’t answer. I turn to ask Isaiah, but for the first time, he’s studiously avoiding me.

The marina, a sprawling network of floating docks bookended by the lighthouse and the commercial jetty, runs the length of the western edge of the island. As we approach, I can see a lone worker scrambling up and down the jetty, prepping for the ferry’s arrival. I guess Georgia really did lie to us.

Something doesn’t sit quite right with me about that. I don’t doubt Isaiah. I know it’s not unusual for local businesses to try to make a few extra bucks off a production—not for nothing are contingencies built into the budget. But it feels like there’s more to Georgia’s trick. The guys on the boat—they’d laughed about it. Like it was a joke.

Then again, guys like that will laugh at anything.

I scratch absently at my forearm. I’m probably just imagining things. This is why I need a movie to work on. If you don’t give me a story to tell, I’ll make one up.

The captain guides the boat into an open slip. He hops down to the deck and moves quickly to secure the lines, displaying the same rote efficiency he used to release them back in Lewes.

I check my watch. Twenty-seven minutes travel time exactly.

When I look up, I spot a trim figure hurrying toward us. A woman, I think—probably a PA coming to pick us up.

Not that PAs have to be women, I’m not saying that. I just mean that, generally, this kind of job would be given to one of the less skilled members of the crew.

Not that PAs are generally unskilled—I’m not saying that either!

Well, no, that’s not true. They are. But there’s nothing wrong with that. Everyone has to start somewhere, right?

Anyway, the woman—whatever her title is—is rushing toward us, her hands waving, her mouth moving. It takes me a second to register what she’s saying.

“Are you fucking kidding me, Isaiah?”

Next to me, so quietly I’m not certain I’m not imagining it, Isaiah lets slip the slightest huff of irritation.

On the dock, the captain checks the last line and heads back toward the stern. When he passes the woman, she shies away like he’s made of spiders or scorpions or something that crawls down from your scalp to lay eggs in your ears. I glance at the captain, curious, wondering what she finds so offensive about him—and if he’s offended by her offense—but his chin is tucked to his chest, as usual, and he’s showing no signs of distress.

I study the woman with fresh eyes. If she’s yelling at Isaiah like that, she’s definitely not a PA. So what is she? If this movie had a different director, I might peg her for an actress. She’s certainly pretty enough, with golden brown skin and dark, lustrous hair that falls to her shoulders in an enviably can-you-believe-I-just-woke-up-like-this wave. She’s not wearing any makeup that I can see, but why would she, her brows are perfect, and according to Amy that’s really all you need. She appears to be younger than me, but I know better than to assume that tells me anything about her actual age. Still, when it comes to leading ladies, Tony has very predictable type, and South Asian—stunning though this woman may be—is not it.

Maybe she has a supporting role?

“You said you were chartering a boat,” she says, her tone arctic.

Isaiah nods stiffly. “Which I did. As you can see.”

“You didn’t say you were chartering this boat.”

“I don’t know what to tell you,” he says, rubbing the back of his neck, a gesture I’m beginning to suspect is a sign of consterna

tion. “It was the only one available.”

“Don’t you know how much trouble we could get into?”

“A lot less than if I hadn’t gotten her to the island tonight.”

“Seriously, Isaiah?”

He grabs my suitcase and starts down the dock. The woman stomps after him. After a brief moment of indecision—shouldn’t I say something to the captain before I go?—I shoulder my backpack and follow.

That said, I don’t exactly make an effort to catch up with them. I find, generally, that it’s best not to pay too much attention when people are yelling at each other. They’re just going to say things they don’t mean, and that’s a hard thing to keep in mind if they start yelling about you. Better not to listen in the first place.

As I walk, I slip my hands behind me and rub my fingertips against each other, just a little, running my thumb from index to pinky finger and back again, a quick one-two-three-four, one-two-three-four. I let the rest of my senses go soft. Soon, their angry voices are swallowed up by the soundscape, until their words aren’t even words anymore, just noise, no more meaningful or necessary than bird chatter, dripping water, the grind and slosh of a dishwasher.

I tip my face up to the sky. A few stars are out.

I think I can see Jupiter.

It’s the silence that snaps me out of it.

I turn around, disoriented. Isaiah and the woman are twenty feet behind me, staring at me with wide eyes. I check the front of my shirt, again, reflexively, just to be sure.

“What?” I ask.

They exchange a look, then close the distance between us with startling speed, picking up their argument where they left off.

“Did you pay with a card?” the woman asks.

“No,” Isaiah says.

“Did you get a receipt?”

“No.”

“Does he have a log?”

“I tore out the page.”

“Well that’s something, I guess.” Apparently satisfied, she sticks a hand in my direction. “You must be Marissa. I’m Anjali. We spoke on the phone.”

The name rings a bell, but Nell knows better than to let me get on the phone with anyone. “I think that was probably my agent,” I say.

She shrugs. “Same diff. We’re thrilled you’re here, et cetera, et cetera. Is this really all your stuff?”

“Yes?”

She squints at my compact rollaboard. Next to Isaiah, it looks like children’s luggage. “Which are you, hopelessly optimistic or hopelessly pessimistic?”

“I don’t understand the question.”

“It doesn’t look like you intend to be here for long.”

“I’m just really good at folding things.”

She gives me the insubstantial smile I often get when I accidentally sound like a smart-ass.

“Let’s hope that’s not all you’re—”

Her voice is drowned out by the brassy wail of a marine horn. We turn toward the jetty and watch as the main ferry comes into view.

“Isaiah,” Anjali says after a moment. “What the fuck is that?”

“What do you know,” he says, evenly. “I guess it’s running after all.”

Anjali’s shoulders slump. “Do I even want to know?”

“Wouldn’t tell you either way.”

She shakes her head. “Whatever. Let’s go.”

She makes a sharp, irritable gesture with her right hand and changes course, heading for the tidy commercial stretch that runs the length of the marina. It’s populated by all the tourist-oriented businesses you’d expect from a vacation destination: a visitor center, an ice cream parlor, an antique shop, a high-end consignment store. Even though it must be almost eight thirty, everything’s still open.

The Italian restaurant is the busiest of the bunch. Il Tavolo, it’s called, which I find faintly annoying—I count at least four tables in the alfresco dining area alone. There, three women, all dressed for a night out, are splitting a straw-wrapped bottle of wine. We’re too far away to hear what they’re saying, but the topic must be an easy one: Their conversation is bright and lively and unceasing, punctuated not, as mine are, by awkward pauses and stammered apologies, but by crystalline peals of laughter.

I remind myself that if I were editing a movie, a scene like this would be a pain in the ass. All that overlapping dialogue—more trouble than it’s worth, really.

It’s probably no less annoying in real life.

Probably.

The women pretend to ignore us as we pass, but I don’t miss the way their eyes flick in our direction and back again.

Anjali stops in front of the nail salon, where a black Escalade has been parked diagonally across two and a half spots. She tosses Isaiah the keys; he snatches them out of the air without looking.

I barely have time to strap myself in before we’re pulling out of the marina and onto what Anjali informs me is the island’s sole road.

“It runs along the island’s perimeter,” she explains, sourly. “So you can’t go across the island—you have to go all the way around.” She stabs her finger in the air and sketches an exaggerated circle. “Like a fucking rotary phone.”

I glance out the window. There’s just five feet of shoulder and a battered metal guardrail between us and what appears to be a fairly abrupt drop-off. If Isaiah’s attention slips for just a second—

I crack my window open, just a bit. Just in case.

I peer down at the water.

I open the window a little more.

“I’m not going to drive into the ocean,” Isaiah says, his voice a low rumble.

“I was just getting some air,” I say.

“You were establishing an escape route.”

“A fringe benefit.”

I drag my eyes away from the rearview mirror and realize Anjali has twisted around in the front seat. She’s watching me intently.

I pretend to be very interested in the big building that looms in the distance. “Is that where we’re going?” I ask.

Anjali follows my gaze, nods. “It’s the only place to go, really.”

“What is it?”

“A hotel.”

“Is it where we’re staying or where we’re shooting?”

“Both.”

The tension I’ve been carrying in my neck and shoulders drops by about 5 percent. Hotels are good. I know what to expect from them. High-end, low-end, they’re all basically the same: a bed, a TV, a Bible. Spaghetti and meatballs on the kids menu. I can work with a hotel.

Bed and breakfasts, that’s another story.

Something up ahead flashes white. A sign. Hingham House. One mile.

“Why is that name familiar?” I ask.

“Because it sounds like something out of Shirley Jackson?” Isaiah says.

Anjali stares at him for a moment, then looks back at me. “No one uses its real name,” she says. “They just call it ‘The Shack.’”

“Why?”

She throws up her hands. “Rich people.”

I still don’t follow, but I don’t ask for clarification because something about this place is definitely pinging at my memory—but how? I’ve never been here before. Something from a movie, maybe?

“The Shack,” I say, slowly, feeling my way around the words. “On Kickout Island.”

“Yeah,” Isaiah says, “the brochure really writes itself.”

Anjali groans. “Enough. I didn’t hire you for your commentary.”

He says something sharp in return, and then she’s smirking back, and I tune them out again, automatically, wondering—not quite idly—if they really don’t like each other or if they really do like each other. I’ve always had trouble with that particular distinction. Whoever decided flirting should look like fighting has an awful lot to answer for.

They’re sti

ll squabbling twenty minutes later, as Isaiah steers the car through two low pillars of stacked stone and onto a cobblestone driveway that just barely rumbles the Escalade’s suspension. We pass a parking lot packed full of trucks and trailers, a copse of trees, a boathouse, a hedgerow. Finally, the hotel comes into view.

I press my face against the window to get a better look.

At first, I can’t quite make out if I’m looking at one building or several: The hotel appears to consist of six or seven architecturally distinct structures all smooshed together. In the center is a grand, soaring portico supported by four scrolled white columns; behind that, a perfectly symmetrical four-story clapboard box with dormer windows; behind that, a six-story Victorian cupola with a widow’s walk and two round windows set in a gray slate roof.

I wonder how far back it goes. Who knows what else might be behind there. A medieval guardhouse, maybe, or a Taco Bell.

Isaiah pulls the car up to the portico, and this time I remember to let him open the door for me.

“I’m only letting you do this because I don’t want to take another door to the face,” I say, ducking under his arm.

When I let myself look up at him, I’m hoping to catch a glimpse of one of his smiles. They’re so straightforward, so undemanding. But his expression is so blank it puts me in mind of a prototype android or pathologically fastidious villain. Just like that, his face has been wiped clean of any and all incriminating signs of life.

But that’s how it is, I guess. Now that he’s delivered me to the hotel, his job’s done. He was probably just pretending to put up with me.

“You should hurry,” he says, nodding at Anjali, who’s already halfway up the steps.

I swallow past a tightness in my throat that I choose to attribute to nerves or confusion or dismay or maybe just my body’s realization that it’s been eleven hours since I’ve had anything to eat.

“So that’s good-bye, then?”

Isaiah draws back. “What gave you that impression?”

“You just got really serious all of a sudden.”

“That’s my job.”

“Your job is to be serious?”

He hesitates. “My job is to keep an eye on things.”

Pretty as a Picture

Pretty as a Picture