- Home

- Elizabeth Little

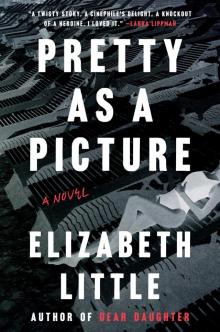

Pretty as a Picture Page 2

Pretty as a Picture Read online

Page 2

The executive props his elbow on the back of his chair and pushes his hair back from his forehead. “You’re certain of that?”

I consider the shot again. “I guess it’s possible the director just thinks it looks cool—”

Nell kicks my chair.

“—but either way, she’s definitely dead.”

The executive studies me over the rims of his glasses. “You’re the first person to bring that up. Everyone else said the white lips were the giveaway.”

“No, I wouldn’t trust this makeup department.”

“Why not?”

I point to Liza’s face. “In the summer, someone with her coloring would freckle. They gave Liza a spray tan, obviously, but the cosmetician adjusted the color, washed it out—probably because her blood would already be pooling in her lower extremities, so she’d be paler than normal. Livor mortis, right? But dying doesn’t make your freckles disappear. They should have painted some in.” I brush my fingertip along her cheekbones. “Right now she looks too much like a movie star, and you don’t want that, not when you’re doing true crime.”

The executive is frowning now, two small lines etched between his eyebrows, and it occurs to me that dragging their makeup department was not, perhaps, the best way to win this job.

Well, at least Nell won’t be able to say I didn’t try.

I open my mouth to thank them for their time—

“What makes you say it’s true crime?” the executive asks.

I glance back down at the photo. Why did I say that?

“Judging by the costume design, it’s a period piece—midnineties, probably? And I figure it’s based on a true story because—yeah, the color hasn’t been corrected or graded, I know, but the overall palette is so deliberate and carefully curated. Meanwhile, that swimsuit she’s wearing is just . . . unbelievably orange.” The answer comes to me the second before I say it. “So I’m thinking, probably, it’s the same suit the real girl was murdered in.”

“Hold on,” he says, “I never said she was murdered.”

“That just stands to reason. Why else would you make a movie about it?”

Now, I may not be a crackerjack conversationalist, but I’m something of a connoisseur of silences. You can, roughly, separate them into two groups: the kind of silence where everyone’s looking at each other and the kind of silence where everyone’s not looking at each other. Personally, I prefer the latter. If there’s going to be cruel laughter, I’d rather it be out of earshot.

The silence that just settled over this room, however, is an extremely undesirable third variety:

Everyone’s looking at something else. Namely, the speakerphone in the center of the table.

Which means they’re scared.

Then there’s a crackle of static, and a voice comes over the line, sealing my fate.

“She’ll do.”

Note: Dead Ringer is produced for the ear and designed to be heard, not read. We strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that’s not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and Suzy’s little brother and may contain errors because lollll, guys, this is not This American Life. Cut us some slack.

SUZY KOH: Hi, everyone, I’m Suzy Koh—

GRACE PORTILLO: And I’m Grace Portillo.

SUZY KOH:—and welcome to this week’s episode of Dead Ringer, the true crime podcast for people who hate true crime podcasts.

GRACE PORTILLO: Seriously?

SUZY KOH: What?

GRACE PORTILLO: I don’t know, that just seems, like, unnecessarily divisive.

SUZY KOH: Fine. It’s also the true crime podcast for people who love true crime podcasts.

GRACE PORTILLO: Okay—

SUZY KOH: And for people who only kinda like them. And for people who don’t even know what podcasts are—but that’s okay, Grandma, I still love you. [pause] Did I miss anyone? Or is that inclusive enough for you?

GRACE PORTILLO: Oh my God.

SUZY KOH: Right, so when we left off last week, Tony Rees’s big-deal dead-girl drama had just hit a snag, losing its highest-profile crew member to date—

GRACE PORTILLO: Not that anyone on the production staff would admit what had happened.

SUZY KOH: The excuse the producer gave at the time was that Tony and his editor had parted ways—

GRACE PORTILLO: Right—“creative differences.” Which doesn’t even make sense! They weren’t even editing the movie yet!

SUZY KOH: Yeah, but we didn’t realize that then. We’d never been on a film set before.

GRACE PORTILLO: What was the crew’s excuse?

SUZY KOH: Probably something to do with not wanting to be fired?

GRACE PORTILLO: Oh. Yeah, I guess that makes sense.

SUZY KOH: So we begin today’s episode with the arrival of Marissa Dahl.

GRACE PORTILLO: Marissa, thanks so much for agreeing to speak with us.

MARISSA DAHL: And thank you for agreeing to stop leaving me voice mails if I came on.

SUZY KOH: Marissa’s a film and TV editor best known for her work with Amy Evans, the award-winning director of Mary Queen of the Universe and All My Pretty Ones.

GRACE PORTILLO: Best known until recently.

SUZY KOH: Well, right. You probably know her as the woman who cracked two of the biggest murder cases of the year.

TWO

Hollywood has just two speeds, “We’ll get back to you” and “We need this yesterday,” and as soon as the speakerphone clicks off, we skip straight past the slow torture of the former and into the unforgiving maw of the latter. The lawyers and agents are all talking rapidly, all at once, about all the things I pay them to think about for me.

“I assume our previous deal memo stands.”

“I’m happy to reopen the discussion of residuals.”

“I’m happy to reopen the discussion of her quote.”

“Her quote’s her quote, Steve.”

There’s an assistant—who can say whose—at my side, tapping on two phones simultaneously, peppering me with questions I barely manage to register, much less respond to.

“Burbank or LAX? Nonstop on American or a layover in Chicago on United? Aisle or window? Six o’clock or seven twenty?”

“There’s nothing tonight?” the executive asks.

I frown. “Tonight-tonight?”

The assistant chews her lip and flicks furiously at her screens. “No—last flight’s at nine forty-five. She won’t make it.”

“Excuse me, I’m sorry, but are you talking about me right now?”

The executive peers at my agent. “Nell, you sure we can’t send her coach?”

She shrugs. “If you think you can find a better candidate, go right on ahead.”

The executive sighs and nods to the assistant. “Book the six a.m. We’ll have our guy meet her there.”

What is happening? Where am I going? Why is everyone acting like we’re launching a military campaign? I glance around the room, but no one appears to be treating this as anything unusual. “Hello? Is anyone going to explain any of this to me?”

The executive spares me the briefest glance. “You’re going to set.”

I make a face like I’ve smelled something sour. “Why? Let the assistant editors handle the memory cards; I’ll get everything set up here for post.”

He waves a hand dismissively. “There are no assistant editors. Tony doesn’t trust them.”

One of the lawyers drops a pile of contracts on the table in front of me and tries to hand me a pen.

I swat the pen away. “I’m sorry, did you say . . . Tony?”

The executive freezes. He swallows, his Adam’s apple dipping behind the crew neck of his overpriced tee. Then he lifts his head

and looks somewhere past my left shoulder.

“Oh, didn’t we mention that? Tony Rees—he’s the director on this picture.”

* * *

—

Live in LA long enough and you’re bound to lose your sense of wonder.

I didn’t grow up in a backwater—not by any reasonable standards—but even so, for a kid in Champaign-Urbana, seeing a celebrity was a big deal. I can still remember the envy and astonishment that rippled through me when I heard that one of my classmates had seen Jennie Garth at the supermarket with her mother.

And Jennie Garth’s from Champaign-Urbana.

After nearly fifteen years here, though, celebrities are just part of the scenery, another thing to not notice on the drive home, and I don’t know what I hate more about my indifferent attitude, the cynicism or the way it sidles right up next to Hollywood cliché. But even so, very occasionally I’ll cross paths with someone so special that those endless, breathless dissections of a five-second glimpse of the back of Jennie Garth’s head make perfect sense again, and for a moment I’ll remember how obscenely lucky I am to be in this business.

Like when Dede Allen smiled in my general direction. Or Agnès Varda shook the hand of someone standing next to me. Once I was introduced to Thelma Schoonmaker, and it turned out she already knew my name.

Then there’s the time I fell into a fountain with Tony Rees.

I didn’t feel so lucky then. It was two years ago, and I was at the Venice Film Festival with Amy. She was accepting an award, and she’d insisted I come with her. We’re a team, she said. You deserve this, too. And I was too much of a coward to say no, so there I was, hiding out in the hotel courtyard, enjoying the symmetry of the colonnade, the palm trees that reminded me of LA, the sky. There was a bench in one corner, but I was walking the outline of the fountain: three sides of a rectangle, two sides of a triangle, three sides of a rectangle, two sides of a triangle.

It was a particularly good pattern. Sometimes, if I walk just the right way—at just the right speed, with just the right gait, in just the right direction—I can lull my worst thoughts into submission.

I was warm, I remember. And relaxed. Happy, maybe.

Then someone cleared his throat.

I recognized Tony immediately, but I know not everyone would. He’s an average, inconspicuous white man in most respects, mid-forties, neither tall nor short nor fat nor thin. His hair isn’t mousy or mahogany or sun-streaked or whiskey-colored. It’s just brown. He has no visible scars, moles, or birthmarks, and only one tattoo: his daughter’s name, on his forearm, in blue script.

Two things set him apart, though.

First, his eyes, which everyone says are strikingly green (“bottle-glass green” is the usual descriptor, though this seems uselessly expansive to me). They’re vivid enough you can guess their color even in the solemn, black-and-white portraiture glossy magazines are forever commissioning of him.

Second, he never speaks louder than a low, intimate murmur. Not ever. Not in interviews, not on commentary tracks, not at awards shows, not even—as anyone who has ever worked with him will tell you, in vaguely stunned tones—on set. No matter the situation, Tony talks to you like he’s inside you.

That’s how Amy once described it, anyway. I’d just say he’s kind of hard to hear.

How the most exacting director in Hollywood manages to make his movies without raising his voice is one of the great mysteries of show business.

We were separated that day by the reflecting pool, a comfortable enough distance that I didn’t mind looking directly at him. He was dressed in jeans and a chambray shirt, the cuffs rolled back, three buttons undone. His tan stopped at his neck, tracing a line where a T-shirt would normally lie; below that, settled into the hollow of his throat, was the silver disc of a St. Christopher medal.

He was watching me, tapping his chin absently with one long finger, his right elbow propped on his left fist, and I can still taste the bile that burst on the back of my tongue when I realized what was happening. This wasn’t the second lead on a network sitcom or the star of a new Verizon campaign. He wasn’t waiting for fro-yo or prodding figs at the farmers’ market or blocking the pasta aisle at Von’s. This was one of America’s most celebrated directors, a man whose work I admired deeply.

And he wanted to talk.

Or at least he looked like he wanted to talk. He wasn’t showing any of the usual signs of impatience: His feet weren’t shuffling; his gaze wasn’t skipping around. But he wasn’t saying anything, either.

Then, I felt it. A growing pressure behind my breastbone, a sensation I knew all too well. I sent up a last-second prayer: Please God, whatever I’m about to blurt out, let it be sophisticated. Clever. Astute. About one of his earlier, lesser-known films. About a technical detail that would give me the chance to demonstrate my own expertise. About, at the very least, the weather.

But God apparently had other things on His plate.

“Did you want to talk to me or did I just happen to wander into your line of sight?” I asked.

His finger stilled. His mouth moved. And his next question was so patronizing it took me a moment to register what he was asking.

“Did you just ask if I’m here for the festival?”

He nodded.

Dammit, I thought, I knew I was too short to wear this jumpsuit. Amy had been very clear that I needed to make an effort, an impression, that I couldn’t just wear comfy pants and a tank top—“This is Italy, Mar”—so I’d gone shopping in Silver Lake before we left. I don’t know much about fashion, but the girl who sold me on the jumpsuit was wearing oversized sneakers and jeans up to her armpits, so I thought I could trust her.

Just how ridiculous did I look? Did I need to worry that he was going to call security? Did I need to show ID? Pull up my IMDb page?

Ultimately, I did the only thing I could think to do under the circumstances—I didn’t like doing it, but I didn’t see any other way to establish my credibility.

I dropped a name.

“I work with Amy Evans,” I said.

Sure enough, Tony’s shoulders drew back and his gaze glittered with new interest.

Might’ve just been the sun, though.

“I’m a fan,” he said, lightly.

I wasn’t sure what to say to this. Obviously he was a fan. He was the president of the jury that had just awarded Amy the Silver Lion.

“She’s very talented,” he went on.

I guess I couldn’t quite hide my disbelief, because he let out a low grunt of surprise.

“You don’t agree?” he asked.

“I’m just not sure why you’re telling me things I already know.” My eyes caught sight of a single gull crossing the sky. I had to wait for it to disappear from view before I could return my attention to Tony. “But I guess you can’t help being a director.”

One of his eyebrows lifted, and an image of Joaquin Phoenix in Roman regalia, his thumb just tipping toward the ground, flashed before my eyes. Tony Rees, I remembered then, could destroy a career with a single phone call—with a single look.

Could and would and had.

But that day, for reasons I still don’t understand, he chose instead to be amused.

His laughter was softer than his speech, softer even than the silky burble of the courtyard fountain, and I took a step closer, listening for the hard, tight tone that would mean he was laughing at me, not with me. When I didn’t hear it, I caught myself wishing—fiercely enough that my pulse skipped at the thought—that he would be called away on some urgent matter so I could count the conversation a marginal success. The laws of probability were not on my side.

“Who are you?”

“Amy’s editor.”

“That’s not what I asked.”

“Then you should have been more specific.”

“Oh?”

>

I explained it as delicately as I could. “Given the context, it stands to reason that the most useful and telling personal detail I could provide would be my area of expertise. You don’t want to know my life story or who my favorite bands are.”

“And if I do?”

“Then you’re out of luck, because I mostly listen to white noise.”

“Anton—”

We turned toward the sound. A few feet to Tony’s left, framed perfectly by the doorway, stood a bird-boned woman in a crisp white dress, her arms akimbo, honeyed hair billowing in a breeze that appeared to blow just for her.

Annemieke Janssen, the hugely popular star of several of Tony’s movies, and also his wife.

She’s extraordinarily beautiful. Delicate. Ethereal. I’m guessing when she gave birth to their daughter, the only sound she made was a single, exquisite gasp.

Tony’s lips pressed together. “Just a second,” he said.

I plucked at the waistline of my jumpsuit and tried not to stare as he made his way to Annemieke.

I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but even I could tell Tony wasn’t pleased—his expression hadn’t changed, but a muscle in his jaw was twitching. Annemieke, however, seemed unconcerned. She kept admiring the toe of her navy stiletto then looking back up at Tony from under her lashes. When she swept her bangs off her face, she used her pinky finger.

I peered down at my own hand, twisting it, palm out, extending my pinky. I lifted it halfway to my forehead before deciding I couldn’t pull it off. I would just look like I didn’t know how a normal human female pushed back her hair.

Pretty as a Picture

Pretty as a Picture